"Soy la sangre dentro de tus venas,

soy un pedazo de tierra que vale la pena."

(Calle 13, Latinoamérica)

Latin American newspapers and magazines are kind of graphic - at least more graphic than those in the United States. Graphic in the pornographic sense and in the bloody/gory sense. During my mission, the glimpses I caught of Paraguayan periodicals were often startling. It's the bloody/gory thing that I want to discuss now.

We've seen a lot of bloody/gory imagery in this class. Vividly visceral depictions of blood, sweat, urine, etc. are found in materials we've studied from Victors and Vanquished to the short stories to The Kingdom of This World to Bless Me, Ultima, to... you get the picture.

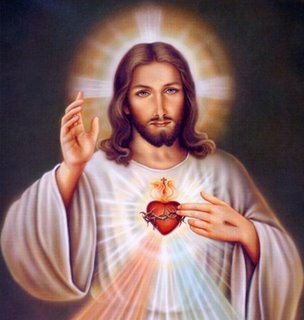

I want to talk specifically about the heart. Hearts are all over the place in Latin America. Not the Valentine-shaped <3 type of heart, but the beating anatomical heart. Catholic images of El Corazón Sagrado de Jesus are everywhere. Recall the heart from Borges' The Circular Ruins. In addition, think about the live performance of Latinoamérica that we watched in class - if you look closely, there's a small screen that shows a fist superimposed over an image of a heart that is beating constantly throughout the song. The larger screen shows lots of different changing scenes, but the smaller one shows the beating heart throughout. The music video shows an underground heart - the aorta and arteries stretch out through the dirt like roots of a tree.

Isn't the song all about roots? About origins? How does the heart relate to that? Hearts are symbols of life and love. Blood is a symbol of inheritance and mortality. All these themes are very important in Latin America, but aren't they important in all cultures? What makes Latin America different - why is there so much visceral realism?

(On a somewhat related note, blood symbolism ties in nicely with my post about fire and water from a couple weeks ago: "...ye must be born again into the kingdom of heaven, of water, and of the Spirit, and be cleansed by blood... For by the water ye keep the commandment; by the Spirit ye are justified, and by the blood ye are sanctified..." -Moses 6:59-60)

soy un pedazo de tierra que vale la pena."

(Calle 13, Latinoamérica)

Latin American newspapers and magazines are kind of graphic - at least more graphic than those in the United States. Graphic in the pornographic sense and in the bloody/gory sense. During my mission, the glimpses I caught of Paraguayan periodicals were often startling. It's the bloody/gory thing that I want to discuss now.

We've seen a lot of bloody/gory imagery in this class. Vividly visceral depictions of blood, sweat, urine, etc. are found in materials we've studied from Victors and Vanquished to the short stories to The Kingdom of This World to Bless Me, Ultima, to... you get the picture.

I want to talk specifically about the heart. Hearts are all over the place in Latin America. Not the Valentine-shaped <3 type of heart, but the beating anatomical heart. Catholic images of El Corazón Sagrado de Jesus are everywhere. Recall the heart from Borges' The Circular Ruins. In addition, think about the live performance of Latinoamérica that we watched in class - if you look closely, there's a small screen that shows a fist superimposed over an image of a heart that is beating constantly throughout the song. The larger screen shows lots of different changing scenes, but the smaller one shows the beating heart throughout. The music video shows an underground heart - the aorta and arteries stretch out through the dirt like roots of a tree.

Isn't the song all about roots? About origins? How does the heart relate to that? Hearts are symbols of life and love. Blood is a symbol of inheritance and mortality. All these themes are very important in Latin America, but aren't they important in all cultures? What makes Latin America different - why is there so much visceral realism?

(source)